Water is a resource that is often wrongly thought to be endless. In Quebec, the ease of access to water and the abundance of water bodies enables it to be used freely. However, water resources in Quebec may be vulnerable to climate change.

In fact, Quebec has seen hydrological drought and low water levels, especially in summer and fall, which means the province may face periods of water deficit.

Although general knowledge of surface waters such as lakes and rivers is well established in Quebec, groundwater is less well understood. However, nearly 90% of inhabited areas and 25% of the population have their water needs met by groundwater.

Marie Laroque, a professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Université du Québec à Montréal and principal investigator for the research chair on water and land conservation, provides an update on knowledge about groundwater in Quebec, particularly in the context of climate change.

The state of knowledge on groundwater

Historically, in Quebec, surface water has been studied much more than groundwater. This is due to the simpler access to both the data and the surface water itself, which is more visible and accessible than water found underground.

In 2008, the government of Quebec began funding groundwater research projects, which built on exploratory work conducted by the Geological Survey of Canada in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The task of mapping and assessing the groundwater resources in almost all of Quebec’s inhabited areas was carried out by several Quebec universities. The resulting research projects have generated many benefits, including the consolidation of training and research activities on hydrology in Quebec, the training of qualified workers, the creation of an open-access database and maps on Quebec’s groundwater, and the consolidation of the Réseau de suivi sur les eaux souterraines du Québec (Quebec groundwater monitoring network).

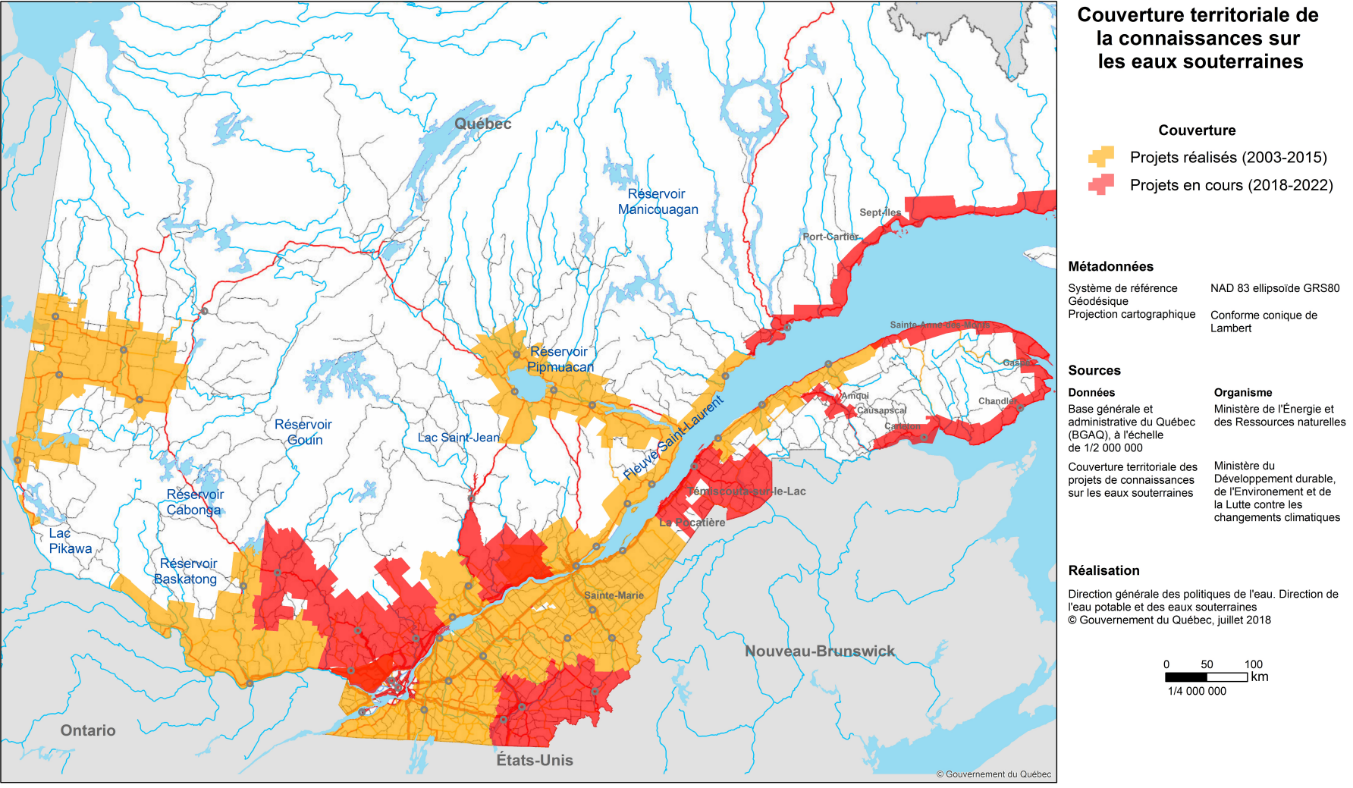

As of 2022, the mapping of almost all the inhabited areas of Quebec has been completed, as shown in the following figure. It should be noted that Quebec’s large size, with areas that can be difficult to access, as well as the expenses associated with acquiring knowledge on groundwater, explain why this process took a significant amount of time compared to mapping the surface water. This mapping is very useful, especially for municipalities, which now have access to data and maps that can provide them with information on the groundwater in their area.

Figure 1: Coverage of knowledge on groundwater. Areas in red have been mapped since 2022 (drawn from: MELCCFP, 2024).

To learn more about the groundwater in your region:

Groundwater and climate change

Since groundwater is renewed by the percolation of water from the surface, it is more indirectly influenced by climate change than rivers and lakes.

Still, the increasing number of extreme weather events, such as intense precipitation, pose a unique challenge: a large amount of water in a short period of time can exceed the soil’s absorption capacity. This situation is exacerbated in areas with low soil permeability, making some areas more vulnerable to declines in groundwater levels.

Essentially, the increase in temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns associated with climate change will impact groundwater. Although the effects of these changes are still relatively small, slight downward trends have begun to emerge in some regions in recent years. For example, from the fall of 2020 to the summer of 2021, abnormally high temperatures and low precipitation led to lower-than-normal groundwater levels in many regions of Quebec.

In the coming decades, the intensification of climate change could significantly affect the renewal of groundwater and its interactions with the other components of the water cycle. However, the effects of climate change on groundwater are not easy to predict.

Although some trends are emerging, research is underway to better understand the dynamics of groundwater and deepen our understanding of the impacts climate change will have on it. This new knowledge can help Quebec to adapt and limit the potential consequences.

Issues on the horizon

Lower water tables may pose a significant challenge for the majority (80%) of Quebec’s rural population who depend on a well for their water supply. This situation not only affects the quantity of water available, but can also reduce its quality. For example, a decrease in groundwater levels can have repercussions on public health, in particular through the spread of diseases associated with contaminated water, such as E. coli infection. Supplying municipalities and farms with the large amounts of water they require could become more difficult as water levels drop.

Natural ecosystems will also suffer from these changes. During low water periods, aquifers can bring fresh water to watercourses that are the breeding habitats for certain aquatic species. However, when groundwater levels decrease, less groundwater reaches these watercourses, leading to an increase in water temperature. This increase can affect the reproduction of fish such as salmonids.

In addition, prolonged declines in groundwater levels, especially after a succession of dry summers, can cause woody species like trees to invade peatlands and wetlands. This phenomenon, called afforestation, contributes to a very localized decrease in groundwater levels along the edges of wetlands. In peatlands, this afforestation not only reduces the amount of water in the peat, but also threatens the biodiversity of these ecosystems.

Research to further our understanding

Much knowledge remains to be gained about the functioning of groundwater systems, particularly in a changing climate. A better understanding of water cycle interconnections is essential.

To this end, major funding has been confirmed for several years to establish an observatory of the entire water cycle across Eastern Canada. One of the objectives of this project is to homogenize data collection on the entire water cycle and make use of it. Eventually, the interconnections of this cycle will be modelled by including each of its components.

This research will ultimately allow us to anticipate the impacts on our communities and ecosystems and enable better adaptation planning for our infrastructure and municipalities.