Heat waves

In Quebec, like elsewhere in the world, human activities such as the use of fossil fuels, deforestation and livestock farming contribute to the intensification of extreme weather events, including heat waves.

The scientific community agrees that increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions combined with urbanization and changes in vegetation cover are causing ever higher temperature extremes.

Definition | Heat waves

According to Quebec’s health and social services network, a heat wave is defined as a period of three consecutive days (or more) during which the maximum and minimum temperatures reach or exceed certain thresholds, depending on the region. These regional thresholds are based on the expected impacts on excess mortality. For three days, the daily maximum temperatures must reach between 31°C and 33°C (depending on the region) and the minimum temperatures must remain above 16°C to 20°C for it to be considered a heat wave.

The extreme heat waves that occurred in Quebec in 2010, 2018 and 2020 left their mark on the province with sudden temporary increases in mortality. According to some epidemiological studies, a 1°C increase in the intensity of heat waves increases the risk of mortality in humans by nearly 5%.

This climate hazard can have many negative effects on people’s health, including heatstroke and cardiovascular and respiratory disorders. Heat waves can also affect mental health.

Factors that cause heat waves

Heat waves are complex meteorological phenomena whose formation is influenced by both atmospheric circulation and various thermodynamic processes.

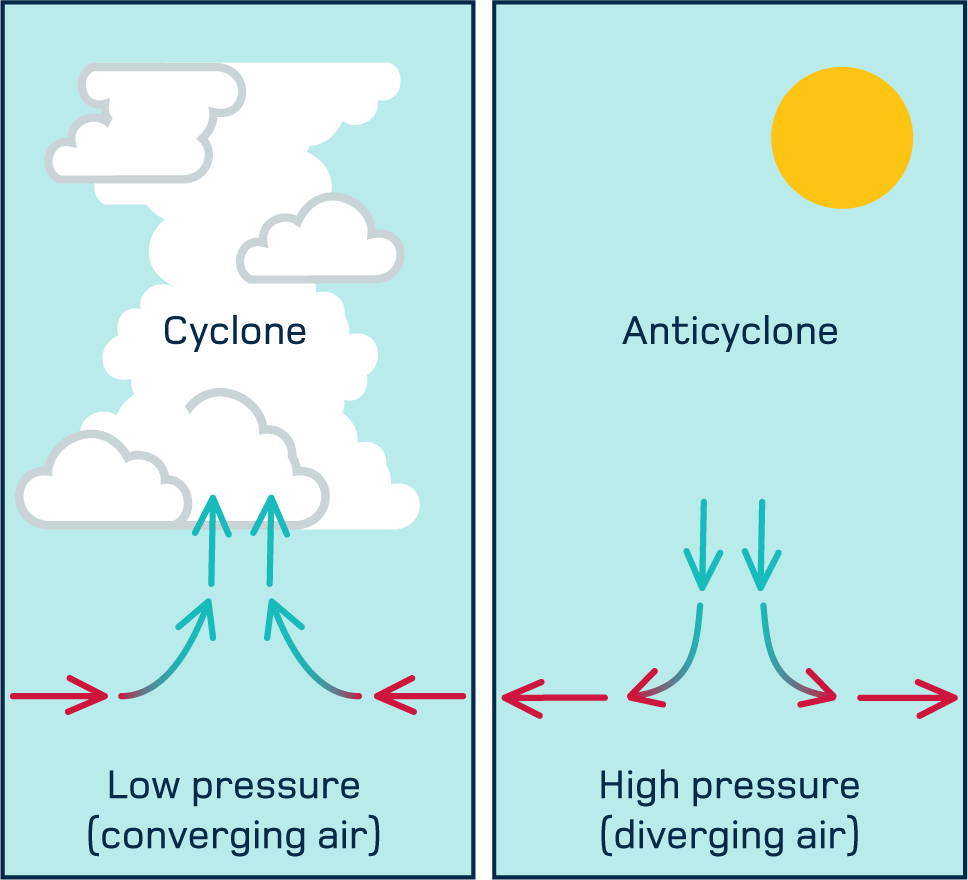

Most heat waves occur when we find ourselves under a stationary anticyclonic weather pattern. These patterns, often called “atmospheric blocking,” prevent the normal movement of weather systems and can last for several days or even weeks. In eastern Canada, 80% of extreme heat events are associated with atmospheric blocks.

Stationary anticyclones are a type of weather pattern that creates conditions making it likely that a mass of hot air will settle and stay put in a region for several days. To be precise, the downward air movements associated with stationary anticyclones cause the air parcels to heat up and dry out. This has the effect of dispelling the clouds, thereby promoting dry, sunny weather, which directly increases the heating of the Earth’s surface.

Some local surface conditions, such as dry soils and urbanized environments, can worsen the effects of extreme heat in a given location. Since evaporation is reduced, most of the energy available at the surface is transformed into sensible heat, causing an increase in the temperature of the ambient air. For this reason, highly urbanized areas have significantly higher temperatures, in particular due to lower vegetation density and impermeable soil.

The historic 2018 heat wave in Quebec

Figure 1 : Map of Quebec representing the extent and duration of the heat wave in June-July 2018 for the affected regions. Source: Government of Québec, 2018.

The heat wave that occurred in Quebec between June 29 and July 5, 2018, was one of the most intense ever recorded in the province. The event lasted for six days in the Montréal region and the average maximum (day) and minimum (night) temperatures during these days were 33.7°C and 22.1°C respectively. The air was particularly humid, the sky was virtually cloudless and the wind was quite weak. As a result of this episode, 210 people lost their lives and several hundred individuals were hospitalized. Note that following this heat wave, temperatures remained high throughout the month of July.

The effects of humidity and heat on human health

Humidity can interfere with the human body’s sweating mechanism, which is essential for cooling. Limited sweating can contribute to greater retention of body heat. It should be noted that heat exhaustion reaches more critical levels during very humid periods of extreme heat, with significant physical and psychological consequences.

Thanks to this project, managers, professionals and planners in Quebec municipalities have a new tool for assessing and mapping the vulnerabilities of the Quebec population to heat waves and hydrometeorological hazards.

This project documents the link between the temperature measured inside the home and various health effects in a population that is vulnerable to heat. The analyses show that the built environment has an influence on temperatures inside the home. The results demonstrate that in very hot weather, i.e. 30°C and above, various symptoms are reported more often compared to during cooler weather.